Courthouse News Service: Federal judge mostly upholds Arizona proof-of-citizenship voting laws

While the judge allowed the laws to stay on the books, she did strike down certain provisions, including those requiring voters to put their birthplace on registration forms.

JOE DUHOWNIK, COURTHOUSE NEWS SERVICE, MARCH 1, 2024

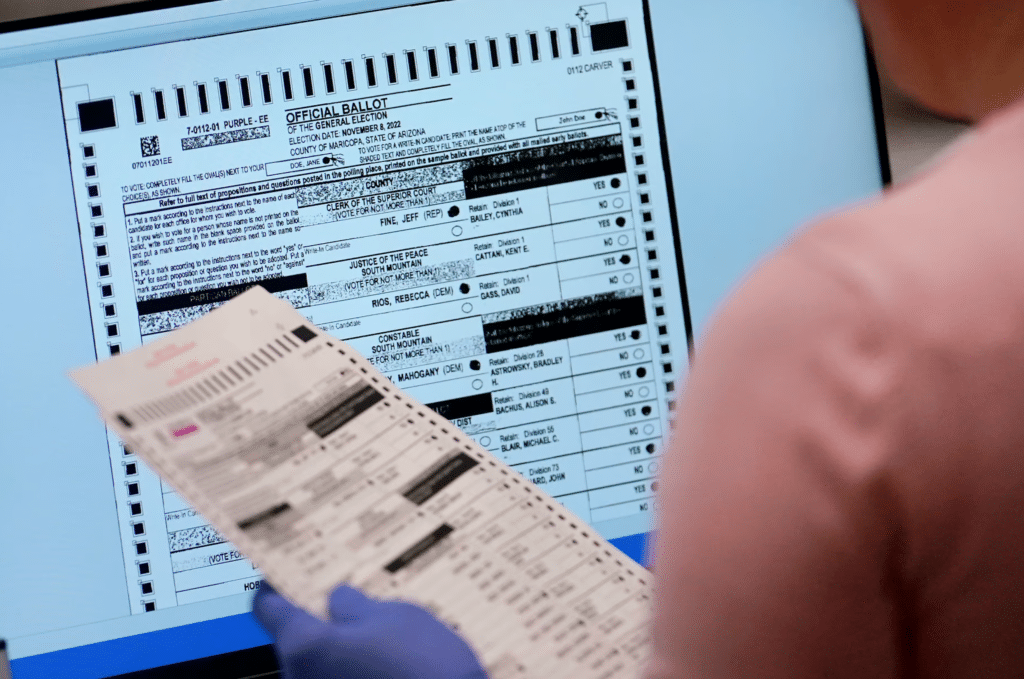

PHOENIX (CN) — Arizona can require voters to provide documentary proof of citizenship to vote in federal elections, a federal judge ruled this week.

The ruling comes three months after a bench trial over the constitutionality of two Arizona voting laws requiring county recorders to cancel the registration and investigate the citizenship status of voters who haven’t provided proof of citizenship. On Thursday, U.S. District Judge Susan Bolton ruled these requirements don’t violate the National Voting Rights Act, nor do they impose an undue burden on the right to vote.

A coalition of voting rights groups, led by Mi Familia Vota, sued the state in 2022 over the two laws: House Bill 2492 and House Bill 2243.

While documentary proof of citizenship for state elections has been required since 2005, these laws extended the requirement to federal elections as well. Bolton, a Bill Clinton appointee, blocked the laws from taking effect for the duration of the trial.

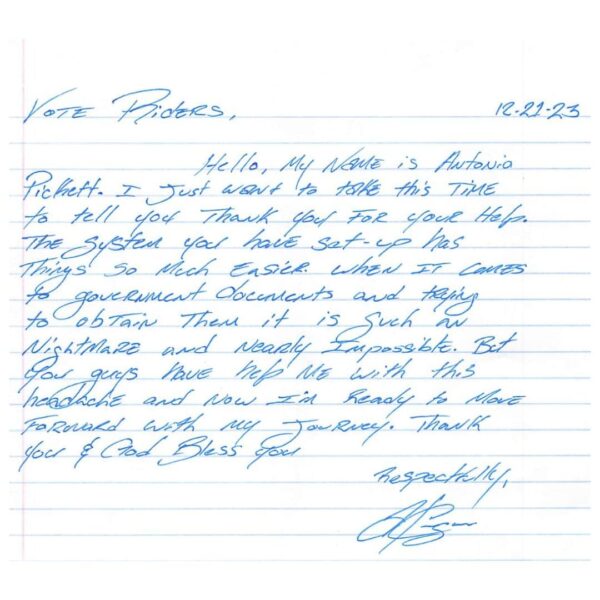

Arizona is the only state that requires proof of citizenship to vote. Ceridwen Cherry, legal director of the nonprofit VoteRiders, called the investigation requirement “voter intimidation.”

“Adding anything that could lead to fear of legal prosecution, that is just going to dissuade voters,” she said in a December interview. “Naturalized citizens are the most likely to experience voter confusion and voter intimidation.”

The plaintiffs collectively argued that the laws are nothing but a “baseless attack” on voting rights based on unfounded claims that noncitizens are committing mass voter fraud. There have been only two convictions of noncitizens voting in Arizona’s history, according to court documents.

Derek Lyons, president of the nonprofit Restoring Integrity and Trust in Elections, countered that the laws are meant to instill confidence in election security.

“Just because there aren’t prosecutions doesn’t mean these things are not happening,” Lyons said in a January interview. “Survey data suggests that noncitizen voting happens more frequently than people would want to believe.”

To back up this argument, Lyons cited a 2014 voter fraud study — though he admitted the study was debunked by the Washington Post because its results were extrapolated from too small a data set.

The plaintiffs also claim that the laws are targeted specifically at Latino voters, who are less likely to have documentary proof of citizenship and are more likely to be naturalized citizens.

Bolton rejected that argument.

“Plaintiffs did not show that the Arizona Legislature enacted the Voting Laws because of any impact on minority voters or naturalized citizens,” she wrote in the order.

Lyons insists that most everyone has the required documents and that those that don’t should have no trouble accessing them.

Cherry called that a “wide misconception.” A study VoteRiders conducted in 2020 found that 12% of voting age Americans didn’t have a valid driver’s license, while 6% didn’t have that or a valid passport. Black and Hispanic people were twice as likely as white people to not have either document.

While it’s known that around 7% of U.S. citizens lack ready access to proof of citizenship, the plaintiffs failed to demonstrate the number of voters the laws will affect, Bolton wrote in her opinion.

“Nor did plaintiffs show that naturalized citizens or people of color are more likely than their White counterparts to lack DPOC,” or documentary proof of citizenship, she wrote. “Assuming all of Arizona’s federal-only voters did not possess DPOC at the time of registration, this would account for less than half a percent of the state’s registered voters.”

Bolton also rejected the argument that obtaining proof of citizenship could be overly burdensome for low-income voters. While obtaining a new naturalization certificate, for example, costs upwards of $500, Bolton reasoned that one need only provide an immigration number if they can’t access a certificate. Further, because 82% of Arizona Latinos are native born, they would only need to pay up to $35 for a new birth certificate.

Although Bolton upheld the laws in general, she did strike down certain provisions, including those requiring voters to include their country of birth, requiring proof of residence and subjecting naturalized citizens to different checks than native-born citizens. These rules violated the Civil Rights Act or the National Voting Rights Act, she found.

Lyons would have liked to see the birthplace requirement stay, arguing against that birthplace is relevant to citizenship.

“If you write that you were born in the country, then you’re a citizen,” he said. “So, it’s easier to confirm your citizenship. If you weren’t born here, then we need more documentation from you. If you weren’t born here, and you don’t have those documents, then it’s more likely that you aren’t a citizen.”

“I think we would all agree we would want noncitizens to be removed from our voting roles,” Lyons added.

Like the plaintiffs, Cherry argued that birthplace has “absolutely no connection” to their citizenship.

Arizona Attorney General Kris Mayes, a Democrat, declined to comment on the ruling. Other parties did not respond to requests for comment.